Monday, November 30, 2009

Moira Edie

Kay, a Gardener

Friday, November 27, 2009

Jose Dysfortuna

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

now is the time to act

The fridges need to protect their place in the kitchen. Those blenders have been creeping up on every surface. The steamers have already been wiped out by the bastards. Who knows who could be next. The mandolins? Surely not the mandolins. We fridges need to do something now before the blenders spread everywhere. We must stop them. Put them in their place!

NOW IS THE TIME TO ACT PEOPLE!

Third Assignment - Character Mapping

"indicat auctorem locus?"

Ovid, EX PONTO, I. VII.

According to the Dartington.org website, the site on which Dartington Hall stands has been continuously occupied for well over a thousand years.

Create a fictional character (with a fictional name) who used to work at Dartington, in any capacity, in any of Dartington Hall's many past incarnations. Roman legionnaire forced to dig latrine? Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst's butler (if they had one)? Write a short epitaph for this character (100 words, first person), and post it to the blog with the characters name as the post title. Write an even shorter 140 character epitaph for your character for Twitter, including your characters name in the Tweet. Write at least three more 140 character sentences about your character for Twitter, which include the character's name and refer directly to the character's relation to the place (Dartington Hall).

Also for next week, photograph or scan your postcards and add them to your postcard story blog posts. Link the sentence(s) in your story that came from another student's zine to the post containing those sentences - see my postcard story post as an example: I've Died And Gone To Devon

The fourth assignment will be to create a map in Google Maps, My Maps. You will need a Google account to do this. Sign up for one and familiarize yourself with Google Maps, My Maps for next class: http://maps.google.co.uk/

Reading:

- On Locative Narrative, Rita Raley (https://twitter.com/ritaraley)

- in absentia, J. R. Carpenter http://luckysoap.com/inabsentia

"Outside the window was like a map, except that it was in 3 dimensions and it was life-size because it was the thing it was a map of. And there were so many things it made my head hurt, so I closed my eyes, but then I opened them because it was like flying, but nearer to the ground, and I think flying is good. And then the country side started and there were fields and cows and horses and a bridge and a farm and more houses and lots of little roads with cars on them. And that made me think that there must be millions of miles of train track in the world and they all go past houses and roads and rivers and fields, and that made me think how many people must be in the world and they all have houses and roads to travel on and cars and pets and clothes and they all eat lunch and go to bed and have names and this mad my head hurt, too, so I closed my eyes again and did counting." Mark Haddon, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, NY: Vintage, 2003, pp 160-161.

Flower Child

She collects mussels from the shore and drinks jasmine tea by the sandbucketful, the flower wavering beneath her lips like a sea anemone. She was always a hoarder of flowers. In her student days, they filled her rickety room. Jam jars and jam jars, and behind them more, of musty rootwater. She picked wildflowers before there were laws against that sort of thing, holed up shy little vole, making her meticulous botanical studies. Now she only picks the flowers in her gardens. She leaves the wild orchids to the bees though. That the landscape could produce such tender flowers, blushing, freckled things.

By contrast, Dartington’s prettiness is cultivated. Totnes, though however unlikely, might have a claim to being the birthplace of British Civilisation. Ardnamurchan is where that Civilisation ends. Hadrian’s Wall might have mostly come down, but it’s there in spirit. The wind gives the landscape something of a facial peel. Trees bent as barbed wire, hillsides scoured away with pan-scrubbers. Used to be a military site, but the shell scars barely scratched the surface of the mountains’ wild silence. Her face is scrubbed blank too. Given a vigorous, rigorous clean with carbolic soap and heather every morning before she sits down behind the potters’ wheel. That’s what she learnt here. It doesn’t seem so long ago, perhaps because, aside from revolutionary spirit and length of hair, she has barely changed. Merely moved from a breeding ground to a retirement home for old hippies, and gradually grown into the landscape.

The march

Parade of shops we skip past, the brown drapery sweeping around your ankles. You laugh and I realise I haven't told you how beautiful you are lately.. We watch the street in the ever changing colours of day and are the sole witnesses of the yellow colour of the arch turning to gold at dusk.

To my vision that street and your arm are the world. I cannot see your old skin or tired eyes, just like I cannot see the old buildings the bright lights are housed in. All is bright and alive and the hill presents no challenges to our new limbs or perfect breath. We march on endlessly, looking ridiculous.. You old in a shaggy coat, me young in a T-shirt with the goose-bumps rising up from my frozen arms.

not where I want to be

The Hills Have Thighs

Sticks & Stones & The Cornish Junta Militia

“So you said,” He said, on one leg. “Please don’t sulk.”

The oak lay where it fell in the winds last autumn. They say. No one had taken it away. I reckon it knew what was coming and couldn’t stand the notion of our leaving. The other oaks that punctuated the meadows of the Dartington Estate were coming into full May glory, and this was the only time I’d ever see them as such. I sat on the walltop whilst He did pigeondances. Playing. We’d fucked in this field. Hopefully we would again. The evacuations to Falmouth were coming. The civilian bombings had been impolite. It was a shame they were hitting the villages; it’s easier to motivate people towards rebuilding a St. Paul’s than a Post Office. And once the Cornish Junta Militia had stolen the gate house cottage – bundled away on a lorry – we knew they were serious, that we’d better take heed. Last night The Great Hall was levelled, bar it’s stone doorway. The door’s gone. So now you’re always walking out. The whalebone beams reminded me of our tree. He kissed me. Nudged me. Playing.

“Please don’t sulk,” He said. We played Pooh Sticks until dark, which was when the lorry returned and dumped the cottage rubble further upstream on the Dart: They’d changed the river irreparably.

“Please don’t sulk,” He said, “They could have drained it."

Dodos

Once upon a time, there was an old witch and a matricidal quintet of Italian chefs who crawled up five million miles of gas piping and out of a drain, all the way from hell. This pleasant culinary flock had flown back to Earth to watch their growing grandchildren (and, more importantly, the second part of the Gordon Ramsey biopic trilogy). The old witch had no purpose.

“How dead and empty are the streets!” she said.

But, alas, in their panic, her comrades had dispersed forthwith and forgotten all about her.

“This is starting to get boring here!” she called.

Then suddenly, horribly, she became struck with the notion that no mortal would ever even recall, let alone appreciate, her contributions to this world. And so, with the intention of writing on the walls her name in their blood, she caught up with her associates and slashed their necks with a machete she kept in her left stocking.

Curses, she thought, ghosts can’t bleed.

In one final act of desperation, she snatched a piece of passing card bearing the letters ‘T-O-T-N-E-S’ and tried to carve her name in tears. Bugger and chagrin, she muttered. Only then did she remember she had forgotten her name and could not cry after all. In the end, she decided to bend one corner of the card.

And shortly after, a northern squad of Hell’s bureaucratic fuzz came and recaptured the escapees, torturing them on the way with nooses made of red tape. The end.

Lost in the Gardens

At the start I was looking for the light. It was nowhere. Just the branches, thick and heavy branches stretching out above and around me like a thousand rakish fingers dotted with leaves that contorted and knotted in their death throes as the autumn air suffocated and froze them. No light, well some light, the moon was above me but choked by clouds it’s light had dwindled until it was useless, just a sphere of cheese in orbit two-hundred and thirty-eight thousand miles above Dartington too dim to even illuminate the face of my watch. What time is it? Have to get through the Gardens, have to get to the Roundhouse. I’ve got a promise to keep and I’m not in the habit of letting people down, well okay, maybe I am but I do try to avoid it as best as I can.

My feet are wet, bloody canvas shoes. I’m kicking up flurries of leafy-mulch with every effortful stride. My straying from the pavement to find a shortcut has epically failed, this side-path is essentially a trail of exposed tree roots that no grass or weed can penetrate. I’m late already. Why aren’t the guiding lights of Lower Close and the Hall beaming through the scattering of trunks and bushes? This is hopeless. I won’t enjoy myself when I get there now anyway; knackered and wet and muddy. I’ll just apologetically get a round in a sit unenthusiastically at a table occupied by smiley, cheery laughing people. Bugger.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

I've Died and Gone to Devon

The Yachts of Salcombe Estuary

Sand blasted daisies sway in the park, their yellow faces smiling at the sun as the sea breeze tickles their petals and the grass dances in rhythm. And I lay back, the children running around me, flicking sand at each other and screeching like the gulls overhead.

By Kate Rolison (as her Blogspot won't let her post, ahhh!)

By contrast, Dartington’s prettiness is cultivated. Totnes, though however unlikely, might have a claim to being the birthplace of British Civilisation. Ardnamurchan is where that Civilisation ends. Hadrian’s Wall might have mostly come down, but it’s there in spirit. The wind gives the landscape something of a facial peel. Trees bent as barbed wire, hillsides scoured away with pan-scrubbers. Used to be a military site, but the shell scars barely scratched the surface of the mountains’ wild silence. Her face is scrubbed blank too. Given a vigorous, rigorous clean with carbolic soap and heather every morning before she sits down behind the potters’ wheel. That’s what she learnt here. It doesn’t seem so long ago, perhaps because, aside from revolutionary spirit and length of hair, she has barely changed. Merely moved from a breeding ground to a retirement home for old hippies, and gradually grown into the landscape.

Dartmouth Castle

I don’t pay attention much, but I can see enough to see the lie of this postcard. Mostly what I see is rain spatters, droplets on glasses, and mist. Even the greenery is grey and faded. At low tide the stippled water runs over rucked sheets. If rucked sheets were river creased black stone; any metaphor will break down under scrutiny. Then the waves come rushing back, breathtaking, thought stopping, white, foam-like Neptune’s horses throwing themselves across the water and breaking their necks on the slimed stones. Spray soaks castle walls and wooden steps seemingly designed to send me slipping and staggering, and I forget the irony, oh the irony, of sunny postcard skies over calm postcard seas.

Choking on the Laughter of Ephemeral ponies

Around this time of year the ponies are particularly guarding over the moor's legacy, there is a sway in their steps as they meander down the ditch. A heady tang I will never forget, we watch the crumbs of our bread and cheese turn to stone as you ask; "Is the sky always this purple?"

And from the Hay I walk on the moon to the hounds that watch over this land. I stop to twist my alphabet into a letterbox, to leave an overdue recollection, and you rush off ahead to churn and mull over your escalating thoughts. We unite again ten minutes in the past, reminiscing five miles into the future whilst fumbling to grasp onto a slice of the present.

We stop to console the young girl at the crossroads; I rest against Bowerman and feel his blood moving. You quake on the featherbed as a thick rolling mist beckons us towards Princetown. Things take a turn for the worse as the prisoners of war pass through us. Then you find us walking over Two Bridges although we are unable to crawl over one.

Watching the granite dance on the Sabbath from atop a headless horse I catch the top hat you throw me, adorn my head as I sink into your inner monologue. Upon feeling the frost for the very first time I turn, and reply; "Yes it's usually purple at this time in the morning." You tell me it's been three hours, but I'm convinced it's been five days.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

VO....YA....AGE

2. There is a much greater freedom in the Dart, a willingness for people to contribute - it felt like i'd opened my mind out.

3. "I am no bird; and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will".

4. The language of the river, the words of the people........tumbling.......tumbling........tumbling.

5. Me the poet, Me the reader, Me the self.

Thursday, November 19, 2009

The Dull Cynic's Guide to the River Dart

The River's waters start their flow at one of Britain's greatest natural beauties; Dartmoor... there's not a decent chippie or pub for miles and miles and miles.

The Clapper Bridges

A form of bridge of prehistoric origin made from slabs of granite that can still be found and traversed today, probably because the council can't be arsed to replace them.

Buckfastleigh

Soon after leaving moorland the Dart flows past Buckfast Abbey where the monks are known to practice beekeeping... as if anybody cares in the slightest about that.

Totnes

And after a whole load of nothing you get to this market town called Totnes. There's some right weird types there, full of the arty-farty lot... but some all right pubs.

Dartington

As if there aren't enough places with 'Dart' in the name and there's an art college nearby too... bloody hippie kids. P.S. The cider press isn't working AN OUTRAGE!

Dartmouth

And now we come to where the River surges out into the English channel, there is a castle but it's pretty small and not really worth the effort. (Also 'Dart' in the name AGAIN)

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Second Assignment - Postcards From Here

"A big bundle of postcards. The curdled elastic around them breaks. I gather them together on the floor.

Some people wrote with pale-blue ink, and some with brown, and some with black, but mostly blue. The stamps have been torn off many of them. Some are plain, or photographs, but some have lines of metallic crystals on them – how beautiful! – silver, gold, red, and green, or all four mixed together, crumbling off, sticking in the lines on my palms. All the cards like this I spread on the floor to study. The crystals outline the buildings on the cards in a way buildings never are outlined but should be – if there were a way of making the crystals stick. But probably not; they would fall to the ground, never to be seen again. Some cards, instead of lines around the buildings, have words written in their skies with the same stuff, crumbling, dazzling and crumbling, raining down a little on the people who sometimes stand about blow: pictures of Pentecost? What are the messages? I cannot tell, but they are falling on those specks of hands, on the hats, on the toes of their shoes, in their paths – wherever it is they are.

Postcards come from another world, the world of the grandparents who send things, the world of sad brown perfumes, and morning. (The gray postcards of the village for sale in the village store are so unilluminating that they scarcely count. After all, one steps outside and immediately sees the same thing: the village, where we live, full-size, and in color.)"

Elizabeth Bishop, "In the Village," The Collected Prose, FSG, page 255.

Assignment: Using a "found" postcard as a starting point, write a postcard story of a maximum of 250 words. You don't have to write the story on the postcard. The postcard must represent (or strongly resemble) a local place. The postcard story must refer to the image and place on the postcard, however tangentially, must tell us something about the place that the image does not, and must use one sentence from another student's zine.

For next week:

- post your postcard story to the blog

- include an image of the found postcard in the post

- tag the post with "postcards" and any other labels you think appropriate

- bring the postcard and a print copy of the story to class

- find and follow each other on Twitter

- rewrite your zine sentences as 140 character tweets

- READING: http://www.geist.com/opinion/geist%E2%80%99s-literary-precursors

"Nothing is more occult than the way letters, under the auspices of unimaginable carriers, circulate through the weird mess of civil wars; but whenever, owing to that mess, there was some break in our correspondence, Tamara would act as if she ranked deliveries with ordinary natural phenomena such as the weather or tides, which human affairs could not affect, and she would accuse me of not answering her, when if fact I did nothing by write to her and think of her during those months - despite my many betrayals."

Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory

Tempest

Home Map: for veiled, sleeping nomads

2. Maple Mao-Tse tung, march uphill, past a steam boat floating a crowd of drunken, aristocratic Liliputins.

3. Walk plaintive meander to cotton woods to the Breton leaves (jot down his sleepy ideas Koreas careers sightseers (for your own rusty valve of inspiration).. checkmate cobble.

4. Skip over Kandinsky pavement, follow the water.

5. Tread a prison bridge and try not to get mud in your pockets.. meat the Eiffel Tower, turn left for front door.

La Riviere Dart

5 sentences and a title

Minimum four colours

nose blunt into the current, memory sediments

a single theory unites all narrow watercourses

at low tide stippled water runs over rucked sheets

emanations rise through slick mud

riverbed ram gut point floodflux

This is where I put the stick in.

Unknown River

Through the depths of the water I reflect far and wide.

Waiting in my world for a guide to step outside.

Darkness is creeping through the city limits.

I will walk directionless, till the unkown end.

So With The Winds Behind Him...

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

The Dart Valley Foot Path

It gets so muddy along the Dart Valley Foot Path it's no wonder all the cows around here are brown.

The need for knee-high high-gloss violet classic Hunter wellingtons soon became overwhelming.

The painful space between the heart and the credit card is probably the soul.

Totnes is pronounced like Loch Ness, only the monster is silent.

The River Dart

At the head of the estuary of The River Dart is the town of Totnes.

The River Dart is home to many different types of wildlife.

Many places along The River Dart are named after it: Dartmoor, Dartmouth, Dartington, Dartmeet.

The valley and surrounding area of The River Dart is a place of great natural beauty.

Stand By Me

RIP Sam Merrington

Had his throat slit.

Thrown off Brutus Bridge.

Found by the Police.

Bandaged with a Body-Bag.

Monday, November 16, 2009

A map of places I should have been but mostly haven't (A map of the River Dart and Environs)

Meanders, bends in the river, don't last forever. When there is a flood and the river cuts across the meander my house will be underwater.

Totnes is rather nice, or so I am given to understand. Mostly it's just a long way to walk, and I don't go there.

The sea is another place I understand is rather nice, another place which is a long way to walk.

My Five Sentences

I savour the slight taste of Southern comfort, but my being yearns for more.

Beside the water's edge my fingers puncture the river's skin, striving to connect with something natural.

He condems me in a momentary look, uncontainable sterile tears; I crave to caress the dirt.

This the most achingly beautiful place to come across a little death.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

First Assignment - A Dart River Zine

The map may be hand drawn, photocopied, scanned or downloaded; the map may be realistic, statistical, abstract and/or wildly inaccurate, so long as it refers to the real River Dart. The zine must have a title and must contain five complete sentences, each of which must refer to a specific point on the Dart. The zine may contain any number of images.

For next class:

- bring 20 folded photocopies of your zine to class.

- post your zine title and five sentences - in the order they appear in the zine - to the Darting Blog.

- create Twitter and Gmail accounts.

- read: first two Darting blog posts

- read: The Landscape of Ancient Rome: http://www.brynmawr.edu/library/exhibits/antiquity/use4.htm

Thursday, November 5, 2009

In the Beginning there was the Mini-Book

I grew up on a farm in rural Nova Scotia, Canada. Every story I set out to tell starts off that way.

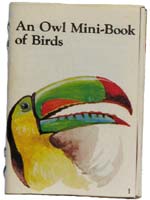

When I was about six years old I had a subscription to a popular Canadian children's magazine called Owl. In one issue, they had a page you cut out, cut up and collated into a mini-book about birds. In 32 pint-sized panels The Owl Mini-Book of Birds introduced twenty-seven orders of birds beginning with the most primitive, flightless birds, and ending with the most advanced, perching birds. I’ve moved house at least 12 times since, but somehow that wee book never got lost in the shuffle. I still have it.

In high school I painted horrible abstracts in acrylics on canvas board, wrote excruciating poetry and studied classical guitar. I could sight-read music, but am completely tone deaf so a career in music was out. It was a toss-up between writing and visual arts until, when I was fifteen going on sixteen, I spent a summer in New York studying life drawing and anatomy at the Art Student’s League. I decided to apply to art school.

I moved to Montreal to attend Concordia University. For four years I worked at the Concordia Fine Arts Library. There I became simultaneously addicted to the disordered stacks of the now defunct Norris Library and the Fine Arts Slide Library photocopy machine. I used the hell out of that photocopy machine. I carried obscure anatomy books out the library by the armload, photocopied all the diagrams and returned the books unread. There were complaints. I almost got fired a number of times. For more on my tawdry affair with the photocopier, read: A Little Talk About Reproduction.

This was in the early nineties, before personal computers came along and made themselves accessible. The drawing classes at Concordia were not quite on par with those at the Art Students’ League of New York. I took an excellent collage class with David Moore. There were photos I didn’t want to cut up. So I photocopied them. There were books I didn’t want to cut up, with anatomical diagrams in them more beautiful than anything I could draw, and there were also diagrams for all my other favourite things: botany, embroidery, analytical geometry, you name it. So I photocopied them, called them "found drawings" and found uses for them.

The first mini-book I made as an adult bore the slightly adult title, Bound For Pleasure. It was based on a poem of the same name and was illustrated with an erratum of diagrams ranging from a garter belt to a bandaged foot. The poems got better over time. The collection of found drawings grew. In art school I made four mini-books: Bound for Pleasure, The Confrontation, The Probability of Mummification, and The Basement Family Pharmacy. They’re no longer in print. Mostly I gave them all away.

In 1993 I discovered the Internet, got a Unix shell account and set out to learn everything there was to know about computers. By 1994 I was no longer working at the Slide Library and thus no longer had illicit access to an after-hours photocopy machine. In 1995 I did a 10-week thematic residency at the Banff Centre, which was call the Banff Centre for the Arts back then.

The theme of the residency was: Telling Stories, Telling Tales. The first story I told them was that I was a writer, which, as far as I knew, I was not, but they let me in anyway. At Banff I attempted to make a number of mid-sized mini-books using the computer, but they never went anywhere. I made this one book based on a circular story. Because it was a book, when people got to the end they just stopped, because that’s what you’re supposed to do with a book. Then the guy in the next studio over pointed out that if I made it into a web page I could link the last page to the first page so the reader could keep going around and around. So I did. My first ever electronic literature project was designed for Netscape 1.1 and it still works: Fishes & Flying Things.

I didn’t even think about making another mini-book for years. Too busy paying off my student loan. Luckily web art led to a few marketable skills. I’ve since worked in every aspect of the Internet industry, as artist, designer, programmer, teacher, consultant, and even, once, a three-year stint as the manager of a multi-national web development team.

After three years in the corporate world I never wanted to look at the web again. So I began writing a novel. About eight months in, I realized how long it would take. Needing to finish something immediately in order to sustain my sanity, all of a sudden I found myself making a mini-book. Not surprisingly, that book, Down the Garden Path was all about how incredibly long it takes to "make a thing which then exists and maybe it is beautiful."

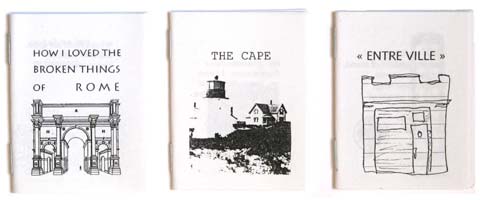

Once the post-corporate traumatic stress disorder has worn off, I began making electronic literature again. My first novel came out in the fall of 2008. It remediates texts from four previously "published" mini-books. Three of the most recent mini-books are based on web projects: Entre Ville, The Cape, and How I Loved the Broken Things of Rome. The web is nice, but nothing beats cutting stuff up with scissors.

I distribute these and other mini-books in person at readings and other events, through various ongoing postal zine exchanges, at Expozine, an alternative press fair held in Montreal every year, and through the DISTROBOTO, a network of cigarette machines repuropsed to sell cigarette-packaged-sized art for $2 at various cafes, libraries and music venues around Montreal.

Or just ask me next time you see me – there are usually some zines in my purse.

. . . . .

Introduction: Mapping Web Words

Notions of place pervade my fiction writing and maps have long featured prominently in my web-based electronic literature, operating (often simultaneously) as images, interfaces and metaphors for place. My most recent work involves the mapping my most immediate surroundings, my Montréal neighbourhood, Mile End.

Entre Ville [2006] and in absentia [2008].

[Mile End, Montreal, Quebec, Canada]

I moved to Montreal in 1990 and have lived in the Mile End since 1992. I have been using the Internet as a medium for the creation and dissemination of experimental texts since 1993. I made my first web-based writing project in 1995. And I made my first Montreal-based project in 2006. Given my preoccupation with place, why did it take me so long to take up the topic of Montreal in my work?

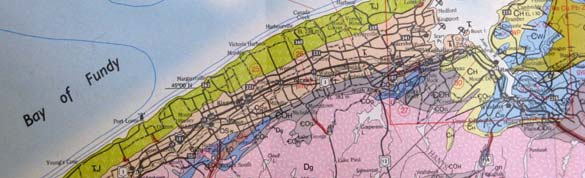

[Geological Map of the North Mountain of Nova Scotia]

I was born on a farm in rural Nova Scotia. I went to a three-room schoolhouse - there were six kids in my grade. In those days, in those parts, people used to say: "You're not from here until you have a grandfather buried here." My parents were immigrants, so even where I came from, I came "from away."

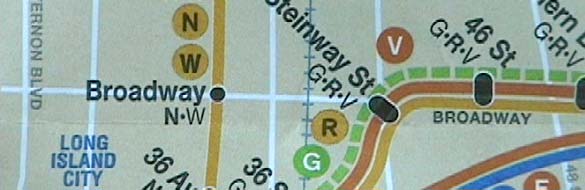

[NYC MTA Subway Map of Long Island City, Queens]

I spent most summers in New York City visiting my maternal grandparents. They lived in a high-rise apartment building in Queens. I thought they were immigrants, because they had such thick accents, but it turns out everyone in New York City talks that way. It took me a long time to figure out that in New York, I was the one with a foreign accent. I felt even less at home on Cape Cod, where my father's mother lived. Canadian novelist Anne-Marie MacDonald describes this condition of chronic displacement in her 2003 novel, As the Crow Flies:

If you move around all your life, you can't find where you come from on a map. All those places where you lived are just that: places. You don't come from any of them; you come from a series of events. And those are mapped in memory. Contingent, precarious events, without the counterpane of place to muffle the knowledge of how unlikely we are. Almost not born at every turn. Without a place, events slow-tumbling through time become your roots. Stories shading into one another. You come from a plane crash. From a war that brought your parents together.

Anne-Marie MacDonald, As The Crow Flies, Toronto: Knopf, 2003, page 36.

It was the Vietnam War that brought my parents together. My father was draft-evader. And, we soon discovered, a marriage evader. After my parents divorced we moved around a lot: every year a new place, new house, new friends, new school. Perhaps this explains why my short stories are so short and why there are so many of them.

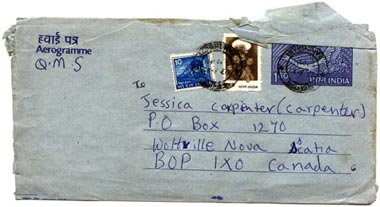

When you grow up in a different country than every one you're related to you write a lot of letters. I'm pretty sure this is how I became a fiction writer: I kept trying to explain where I lived to people who'd never been there before. I wrote a lot of letters to my grandmother in New York City. She rarely wrote back. I guess she felt that New York City, centre of the known universe, needed no further explanation. I corresponded regularly with pen pals in Italy, India and Somalia, and generally spent my time wishing I were somewhere else.

One of my favourite books of all time is The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, illustrated by Jules Feiffer. The main character is a boy named Milo, who didn't know what to do with himself - not just sometimes, but always. "Wherever he was he wished he were somewhere else, and when he got there he wondered why he'd bothered." One day Milo comes home from school and finds an enormous package in his room containing the following items: One genuine turnpike tollbooth; three precautionary signs; assorted coins for use in paying tolls; one map, up to date and carefully drawn by master cartographers, depicting natural and man-made features; and one book of rules and traffic regulations, which many not be bent of broken. Having lots of time on his hands and nowhere better to be, Milo assembles the tollbooth, hops in a small electric automobile he just happened to have kicking around in his room, drives through the tollbooth and proceeds to have many clever and pun-filled adventures. He befriends a watchdog named Tock (tic-tock, tic-tock). Together they travel through Dictionopolis to Digitopolis and (I hope I'm not giving too much away) rescue Rhyme and Reason from the Mountains of Ignorance. No one told him it was impossible to do this until after he'd done it!

One of the three precautionary signs that came with the Phantom Tollbooth advised: HAVE YOUR DESTINATION IN MIND. Milo consulted the map, also provided:

It was a beautiful map, in many colors, showing principal roads, rivers and sear, towns and cities, mountains and valleys, intersections and detours, and sites of outstanding interest beautiful and historic.

The only trouble was that Milo had never heard of any of the places it indicated, and even the names sounded most peculiar.

"I don't thing there really is such a country," he concluded after studying it carefully. "Well, it doesn't matter anyway." And he closed his eyes and poked a finger at the map.

[A Map of the Literary Landscape of The Phantom Map, by J. R. Carpenter]

[A Map of the Literary Landscape of The Phantom Map, by J. R. Carpenter]The first time I read The Phantom Tollbooth I was nine years old. I was in the fourth grade. I wrote a book report about it on single sheet of foolscap. It's the only piece of schoolwork I still have from those years. I wrote: "My book took place in an amaganary world witch you enter through the phantom tollbooth. Its realy like a world in a world."

On the back I drew a map of Milo's route beyond Expectations, through the Doldrums, into Dictionopolis, past the Sea of Knowledge, onward to Digitopolis and upward into the Mountains of Ignorance to rescue Rhyme and Reason from the prison there. The map I drew in no way resembles the map provided inside the front cover of the book. I wonder, in retrospect, if I even noticed that a map had already been drawn; so intent was I on envisioning for myself this "amaganary" world.

HAVE YOUR DESTINATION IN MIND.

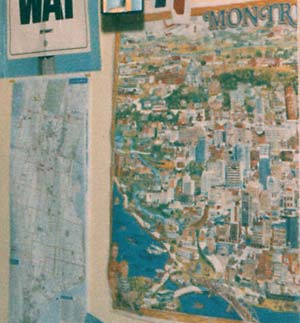

I was twelve years old when I decided I'd move Montréal. Montreal might just as well have been "amaganary" given how far away it was from my reality. At the time, no one I knew had ever been anywhere. Somehow I procured a cartoon map of the city depicting giant caricatures of famous Montrealers romping Godzilla-tall through the streets. The only one I recognized was Mordecai Richler, looming large over Saint-Urbain Street, his mugs well known to me from the back over of Jacob Two-Two and the Hooded Fang.

[Cartoon map of Montreal. Left: in one house, the cartoon map of Montreal hangs above my bed next to a map of Manhattan. Right: in another house the same map hangs over a bookcase]

This map thumb-tacked above my bed I read every Montréal author I could get my hands on, immersing myself in the literary Montréal Irving Layton evoked in his 1985 autobiography Waiting for the Messiah where there was only: "writing poetry and breathing poetry and talking poetry and nothing else had any reality." I got no extra credit in high school, for memorizing A. M. Klein poems. I fell in love with, and secretly wanted to be, the nude girl in Leonard Cohen's 1958 poem Snow Is Falling:

Snow is falling.

There is a nude in my room.

She surveys the wine-coloured carpet.

She is eighteen.

She has straight hair.

She speaks no Montreal language.

What was a Montréal language? I was dying to know.

[aerial view of Montreal]

I moved to Montréal the minute after high school, which hardly seemed soon enough. If you would have told me back then that I'd spend the next fifteen years writing about rural Nova Scotia I would not have believed it. But that, of course, is precisely what happened.

In one of my earliest electronic literature projects, The Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls [1996] a map of Nova Scotia forms the central image of the work and serves as the interface of the opening page. I began writing the narrative text of Mythologies in 1994 and quickly realized that not only did the story have no real beginning, middle or end, it did have lots of diagrams and intertextual incursions that I had no idea how to insert into the narrative.

Further, as I soon discovered, it's quite difficult to get a short story published in print - getting a story with pictures in it published in a literary journal was next to impossible. So I set out to find a medium better suited to my needs. In an essay published that same year, "What's a critic to do?: Critical Theory in the Age of Hypertext", George P. Landow observed:

Further, as I soon discovered, it's quite difficult to get a short story published in print - getting a story with pictures in it published in a literary journal was next to impossible. So I set out to find a medium better suited to my needs. In an essay published that same year, "What's a critic to do?: Critical Theory in the Age of Hypertext", George P. Landow observed: The very idea of hypertextuality seems to have taken form at approximately the same time that poststructuralism developed, but their points of convergence have a closer relation than that of mere contingency, for both grow out of a dissatisfaction with the related phenomena of the printed book and hierarchical thought.

I built the hypertext version of The Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls in 1996. The layout of the map interface on the main page was inspired by the paper placemats one used to find in tourist restaurants around Nova Scotia - an outline of the provence a map dotted with attractions. The narrative structure as a whole owes much to the Chose Your Own Adventure novels that were popular when I was a kid in the 1980s. The reader could enter the story at any point, and read in any order. Within the narrative, I used geological metaphors to distance myself from Nova Scotia, and childhood in general, by relegating them to an even more distant past.

I built the hypertext version of The Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls in 1996. The layout of the map interface on the main page was inspired by the paper placemats one used to find in tourist restaurants around Nova Scotia - an outline of the provence a map dotted with attractions. The narrative structure as a whole owes much to the Chose Your Own Adventure novels that were popular when I was a kid in the 1980s. The reader could enter the story at any point, and read in any order. Within the narrative, I used geological metaphors to distance myself from Nova Scotia, and childhood in general, by relegating them to an even more distant past. In some other millennia, the southern shores of Nova Scotia likely kissed the lip of Morocco or nuzzled below the chin of Spain. The force of their embrace was evidenced by a great mountain range, which slid down the long fault of their tectonic bodies...

[These are strange times indeed, when mountains love oceans...]

Cartography is arguably a literary invention - maps offer a singular point of view defined by a specific vocabulary. We imagine our anarchic, moveable, anonymous world in the guise of a readable map. And we labour under the illusion that we can know the world by naming it. Looking back at my early web projects, I see them now as "sites" of longing for belonging, small stand-ins for home.

Many of my early web works were in black and white, because that's what colour photocopies come in. For a digression into my love of the photocopy, read: A Little Talk About Reproduction.

Many of my early web works were in black and white, because that's what colour photocopies come in. For a digression into my love of the photocopy, read: A Little Talk About Reproduction. The Cape [2005] has a similar visual aesthetic to Mythologies, in part because some of the sentences in The Cape had been kicking around in my brain since the early 1990s. The story seemed too simple to count as a story until I found a copy of a Geologic Guide to the Cape Cod National Seashore from 1979. The images from this scientific publication became the stand-ins for non-existant photographs from the Cape Cod based branch of my family. Because The Cape is in the first person, people tend to think it is a true story. Cape Cod is a real place, but the people and events in The Cape are fictional. The maps are not to scale and the photographs have all been retouched. The moving images that resemble old home movies are actually still images being "pushed" across the screen by a DHTML time line. I tend to avoid Flash, and other software solutions. The more commercial, proprietary and predatory a place the Internet becomes, the more committed I am to using it in poetic and intransigent ways.

My grandmother Carpenter lived on Cape Cod in a Cape Cod House. My uncle also lived on Cape Cod but not in a Cape Cod House. The only time we ever went to visit it was winter but we walked on the beach anyway. These events happened so long ago that this whole story is in black and white.

[Roma Atlante Tascabile, Michelin, Edizioni per Viaggiare]

How I Loved the Broken Things of Rome is the most direct precursor to my current body of Montreal-based work. In 2002, after I'd lived in Montreal for a dozen years or so, I was starting to feel quite comfortable there. In order to reflect upn my adopted city, I decided I needed to recreate the experience of arriving in a new city with no knowledge of the language. I went to live for a time in Rome. I had no real plan, except to observe. Rome is among the largest and oldest continuously occupied archaeological sites in the world. Daily life in the modern, overcrowded, polluted, pickpocket plagued capital city of Rome is complicated, even for the locals. Romanticism and pragmatism must coexist. I rented an apartment in a working class neighbourhood where real Romans lived, where few people spoke English. My mundane struggles with public transportation, grocery shopping and the perplexing web of social vagaries reminded me acutely of my experiences, as an Anglophone, when I first moved to Montréal. I came to feel that understanding what was happening around me was a question of overcoming the dislocation of being a stranger. I collected the writings of many other travelers to Rome. In most cases (including my own) writing about the dislocations incurred by being a stranger in Rome is really an act of writing about home. How I Loved the Broken Things of Rome reflects upon certain gaps - between language and understanding, between the fragment and the whole, between the local and the tourist, between what is known (of history, of culture) and what is speculative.

Rome, if one does not yet know it, has an oppressingly sad effect for the first few days. Through the lifeless and doleful museum atmosphere it exhales, through the abundance of its pasts - fetched-forth and laboriously upheld pasts on which a small present subsists - through the immense over estimation, sustained by savants and philologists and copied by the average traveler in Italy, all of these disfigured and dilapidated things, which at bottom are after all no more than chance remains of another time and of a life that is not and must not be ours.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

[Rome Transit Map]

Entre Ville was my first major piece about Montréal. It was commissioned in 2006 by OBORO, an artists-run Gallery & New Media Lab in Montréal, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Conseil des arts de Montréal. To mark this anniversary the Conseil solicited commissions of new works in each of the artistic disciplines that it funds. Tasked with selecting the New Media commission, Daniel Dion - Director and Co-Founder of OBORO - felt that a web-based work had the most potential to be accessible to a wide range of Montrealers for the duration of the anniversary year and beyond. The commission included a four-week residency at the OBORO New Media Lab, where I edited the seventeen short videos included in the project. The resulting work, Entre Ville, was launched at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal on April 27, 2006.

[The Island of Montreal]

Entre is the French word for "between," as in: entre nous, "between us". Ville is the French word for city. Montréal is an old city. It was founded in 1642 and was called Ville Marie until the 18th century. Driving into modern day Montréal, all signs point to centre ville, downtown. For the past fifteen years I've lived north of downtown in a neighbourhood called Mile End. For the past ten years I've lived on Saint-Urbain Street, on the same block Mordecai Richler grew up on. Inadvertently, I have come to occupy the literary landscape of the Montreal authors I read as a child in rural Nova Scotia. Tour busses still drive by looking for Mordecai, but mercifully his larger-than-life cartoon caricature no longer looms over our street.

[Saint-Urbain Street, Mile End, Montreal]

I work at home. My office window opens onto a jumbled intimacy of back balconies, backyards and back alleys. Daily my dog and I walk through this interior city sniffing for stories. Entre Ville is a text of walking, and a walk through texts. There are many authors of our neighbourhood. Some are famous, some less so. Through prose, poetry, photography, drawing, audio, video and various HTML, DHTML, CSS and javascripts, Entre Ville collates these texts, giving fictional, poetic and philosophical voices equal credence. And the neighbours get a say. It's a shared city, after all, this city entre nous.

[My Dog Isaac in our back alleyway]

Clicking on the Bibliotheque Mile End image at the top right of Entre Ville returns a list of authors from my neighbourhood and a selection of quotations from their works that describe the neighbourhood. One neighbour, poet and classicist Anne Carson, writes in The Life of Towns: "Towns are the illusion that things hang together somehow...." Montréal is both literally and figuratively a French-speaking island. The second largest French-speaking city in the world, after Paris, it floats in North America where only 2% of people claim French as a first language. The second largest city in Canada, after Toronto, only 17% of its population claims English as a first language. It's a complicated place to live, especially if you come from away. But things hang together somehow… Montréal's been very good to me.

Clicking on the Bibliotheque Mile End image at the top right of Entre Ville returns a list of authors from my neighbourhood and a selection of quotations from their works that describe the neighbourhood. One neighbour, poet and classicist Anne Carson, writes in The Life of Towns: "Towns are the illusion that things hang together somehow...." Montréal is both literally and figuratively a French-speaking island. The second largest French-speaking city in the world, after Paris, it floats in North America where only 2% of people claim French as a first language. The second largest city in Canada, after Toronto, only 17% of its population claims English as a first language. It's a complicated place to live, especially if you come from away. But things hang together somehow… Montréal's been very good to me.

Entre Ville was a long time in the making. I sketched the line drawing that became the user interface - a block of typical Montréal apartments - in 1992, while apartment hunting in the Mile End. I spent the next fifteen years learning the vocabulary of the neighbourhood. I don't mean the vocabulary of French, English, Italian, Greek, Portuguese, Yiddish or any of the other languages spoken in the Mile End. I refer rather to the cumulative vocabulary of neighbourhood: the aural, audio, visual, spatial, tactile, aromatic and climatic vocabulary of community.

I have attempted to present Entre Ville in this vernacular. To tell it like it is: Ours is not the nicest alley in the neighbourhood, but it's not the worst one either. Kitchen gardens and garbage heaps coexist with wildflowers and dog shit. Graffiti and grape vines vie for attention. Hand-painted signs warn: defense d'achets, defense du stationez. Cooking smells and laundry lines crisscross the alleyway one sentence at a time.

How does one learn the language of all this? One studies, of course. In The Life of Towns Anne Carson writes: "I am a scholar of towns… To explain what I do is simple enough. A scholar is someone who takes a position. From which position, certain lines become visible. You will at first think I am painting the lines myself; it's not so. I merely know where to stand to see the lines that are there."

From the position of my office window I can't help but learn the lives of my most immediate neighbours. Their voices barge into whatever I'm writing. Sometimes they take over. Entre Ville is based on one such neighbour-interrupted poem, Saint-Urbain Street Heat, which was originally published on NthPosition.com, a literary journal based in the UK. In the opening verse of Saint-Urbain Street Heat:

All the kitchen

All the kitchen back doors stand open -

sticky arms flung open -

imploring, in a heat-rashed prayer:

Deliver us unto

the many gods

of Mile End.

Note that Saint-Urbain Street Heat is not quite written in a first person point of view. Our proximity disallows singularity.

In an intimacy

born of proximity

the old Greek lady and I

go about our business.

Foul-mouthed for seventy,

her first-floor curses fill

my second-floor apartment;

her constant commentary

punctuates my day.

We go about our business. Nous autres. We're poor. It's hot. No one has air conditioning. This is common, a shared experience. Saint-Urbain Street Heat is a long hot sweaty heat-wave poem. Many people who have never been to Montréal in the summer refuse to believe how hot it gets. But we know. Our literature is drenched in the sweat of our summers. The Saint-Urbain Street heat is palpable in Mordecai Richler's 1955 novel, Son of a Smaller Hero:

The sky was a fever and there was no saying how long a day would last or what shape the heat would assume by night. There were the usual heat rumours about old men going crazy and women swooning in the streets and babies being born prematurely. When the rains came the children danced in the streets clad only in their underwear and the old men sipped lemon tea on the balconies and told tales about the pogroms of the czar.

Most Montréal apartments have two balconies: one on the street front and one in the back alley rear. A common ground in our oft-divided city, an extra room, a storage space, a slim slice of outdoors for inner city apartment dwellers, the balcony becomes a stage upon which dramas unfold, from which orations issue. In David Fernario's bilingual 1980 play Balconville, three families sit on their balconies in the heat of a Montréal summer.

JOHNNY: "Whew, hot. You going anywhere this summer?"

PAQUETTE: "Moi? Balconville."

JOHNNY: "Yeah. Miami Beach."

Balconville is a Franglais word, Montréal slang. In French, a "balcony" is a galerie. Like the visual art gallery, the galerie is a site charged with potential. It is an in-between space, an entrespace in which the private unfolds in public display. In Nicole Brossard's 1986 novel French Kiss, the balcony operates as a threshold of enunciation: "One struggles without voice to forge a voice the way a wrought-iron balcony suddenly gives access to the city's far-off sounds." Summer long conversations echo across the alleyway in call-and-answer strophe / antistrophe, clothesline curtains reeling in and out between the acts.

Don't be fooled. I have poetic ideas about neighbourhood, not romantic ones. Entre Ville is hot, loud, crowded and dirty. And, much to my surprise, even after 15 years of living in the city, it turns out that I am still rural, solitary and occasionally misanthropic. Writing about my more trying neighbours has given me a soft spot for them though. Two months after the launch of Entre Ville the old Greek lady next door was evicted from her apartment of 23 years; we watched from our balcony as the discarded detritus of her life accumulated in the alleyway, where strangers rifled through for treasures. Including us. Entre Ville has become a document of gentrification and its erasure. Mile End is changing. Our building is for sale. We may very well be next.

I write about my neighbours acutely aware that I write from amongst them. Gossip is rampant on our street, there to overhear, if you're listening for it. Stories pass from balcony to balcony. Voices carry. Word gets around, especially online. Occasionally the neighbourhood writes me an email. Like this one:

I was sitting at my mom's (no internet at home yet) eating millet pie with ketchup (a bit too dry). I clicked on Wannatakepicture. There was my mom's house. There was the window i was staring out of (blankly) moments before. And there was the voice of Mr. G, the Portuguese landlord. Nice garden. Mom was chuffed. J. M.

How one reads or writes the texts and textures of neighbourhood depends entirely on one's point of view. Do you live here? Are you a parent or a child, a cat or a dog, a bicyclist or in a SUV? Word on the street is, novelist Heather O'Neill lives a few doors down from me. Her award winning 2006 novel, Lullabies for Little Criminals, offers up a disconsolate twelve-year-old's point of view of the alley:

The back alley behind Lauren's house looked the way the world would look if a child had built it. Some underwear and a couple T-shirts that had fallen from clotheslines lay on the pavement. A single sneaker was stuck up on a fence post. There was a toy bucket with rocks in it and a sled that had been left behind from a day when there had been snow on the ground. A wooden door leaned against a wall, leading nowhere. There was a lamp and a bathroom sink in the same garbage heap. You'd think that these houses were being blown apart by the wind, the way that pieces of them were lying about. Not one for them would be a match for the Big Bad Wolf.

Whatever I might say about multiplicity, Entre Ville privileges a pedestrian point of view. If you click on the dog at the lower left-hand corner of Entre Ville, you will see a new text appear on the note book page. Sniffing For Stories was written for an interdiciplinary walking tour of Mile End in 2006. Participants walked up the alleyway listening to and audio track of this text mixed with sounds of the dog and the alleyway. In Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit likens walking to writing: "The walking body can be traced in the places it has made; paths, parks, and sidewalks are traces of the acting out of imagination and desire." In The practice of Everyday Life Michel de Certeau suggests that the "ordinary practitioners of the city" cannot read this writing: "They are walkers… whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban "text" they write without being able to read… unrecognized poems…" Perhaps if de Certeau had lived in the neighbourhood he wrote that about he'd have seen things differently. He claims that: "To walk is to lack a place." My dog and I humbly disagree. For the eight-and-a-half years of his lifetime we've been walking up and down our back alleyway:

Whatever I might say about multiplicity, Entre Ville privileges a pedestrian point of view. If you click on the dog at the lower left-hand corner of Entre Ville, you will see a new text appear on the note book page. Sniffing For Stories was written for an interdiciplinary walking tour of Mile End in 2006. Participants walked up the alleyway listening to and audio track of this text mixed with sounds of the dog and the alleyway. In Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit likens walking to writing: "The walking body can be traced in the places it has made; paths, parks, and sidewalks are traces of the acting out of imagination and desire." In The practice of Everyday Life Michel de Certeau suggests that the "ordinary practitioners of the city" cannot read this writing: "They are walkers… whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban "text" they write without being able to read… unrecognized poems…" Perhaps if de Certeau had lived in the neighbourhood he wrote that about he'd have seen things differently. He claims that: "To walk is to lack a place." My dog and I humbly disagree. For the eight-and-a-half years of his lifetime we've been walking up and down our back alleyway:That's eight-and-a-half years of up and eight-and-a-half years of down.

Nine thousand three hundred laps of toenails clicking on cracked concrete.

Trail zigzagging, long tail wagging, long tongue lolling, dog tags clacking.

Ears open, eyes darting, nose to the ground.

We walk like we own the place. We walk to write the place, to collect, collate and annotate the multitude of texts generated by the occupants of Entre Ville. We try to read between the alleyway's long lines of peeling-paint fences spray painted with bright abstractions and draped with trailing vines. In French Kiss Nicole Brossard describes the meta-text of walking as:

Writing that feeds on zigs and zags and detours… Isn't on every streetcorner but roams the streets, traces its course through them… the narration of the inner odyssey in terms of Montréal's geography, its contours and harsh angles, sidestreets and lanes sharing the circulatory problems with the major arteries, from the heart of the city to the epicentre of oneself, the target and motive source.

Entre Ville is a poem. It has been published in print and online, with and with out pictures, and it has been read aloud to audiences large and small in Montréal and places far away from Montréal's back alleyways. In the early days of the Internet, alarmists and advocates alike proclaimed that digital media heralded the end of the book. Yet, as Derrida had already noted in Writing and Difference:

"The question of the book could only be opened if the book was closed… only in the book, coming back to it unceasingly, drawing all our resources from it, could we indefinitely designate the writing beyond the book."

"The question of the book could only be opened if the book was closed… only in the book, coming back to it unceasingly, drawing all our resources from it, could we indefinitely designate the writing beyond the book." In its book iteration Entre Ville is very small. Photocopied and stapled, the Entre Ville mini-book recycles images cut from some children's textbooks we salvaged from the old Greek lady's moving day garbage. It's sold at readings and events and through DISTROBORO, a neighbourhood network of cigarette machines re-purposed to sell cigarette-pack-sized art for two dollars.

[Mini-Book iterations of How I Loved the Broken Things of Rome, The Cape and Entre Ville]

In its web iteration, Entre Ville's verses scroll the alleyway, popup in windows - altered - and then disappear. The user interface is an image of a blank book upon which a few lines of city have been hastily sketched. Roll the mouse over windows and doors as you might scan your eyes over a cityscape. Occasionally you will catch a glimpse of an interior. And, as in Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, "It also happens that … when you least expect it, you see a crack open and a different city appear. Then, an instant later, it has already vanished."

About six months after the launch of Entre Ville I was invited to submit a new text to le livre de chevet, an anthology on the theme of sleep to be published in French early next year [2009]. I wrote Les huit quartiers du sommeil during a horrible bout of insomnia at Yaddo, an artists' colony in upstate New York. Once again it seems I had to leave where I live in order to write about it.

I moved to Montreal on the night train.

I've lived in eight neighbourhoods since.

Each has had a different quality of sleep.

There are eight hours for sleeping in. There are four quarters in an hour. There are many more quarters in a city. Some quarters never sleep, or so they say. Others seem to be built for dreaming in. The piece begins, as so much of my work has, with the transition from Nova Scotia to Montreal. Specifically, in this case, on the over-night train from Halifax to Montreal:

The night train tunnels termite-determined through silent miles of bark-black forest.

Passengers forage for provisions, restless-long this expedition; minds race ahead,

pace coach and sleeping class compartments listing along the fleuve Saint-Laurent,

dip-slice-glide-lurch-swaying, steady-forward, slow as the Voyageurs' paddles.

These are les huit quartiers du sommeil de Montréal - 1990-2006: Car Crash Sleep, Bamboo Blind Sleep, Waterbed Sleep, Louvered Door Sleep, Purple Parakeet Sleep, Break and Enter Sleep, Gondola Sleep and Greek Sleep. The Epilogue does not take place after all of these sleeps - I have placed it at the end because it is quite possibly one of my first attempts at writing Montreal.

From your house I fled gently, and laughed in the evening.

Too weak to dance. Timid in the aftermath.

I traveled smooth through slow tunnels,

wore thin the scenery and left grey traces.

Dawn. I walked on. Heavy. Soft bones on Sunday.

Slow and sad through the park of young boys slim and quick.

Until finally the rain came, danced three-four time emphatic.

I turned at random. At a stair near a fountain, I turned toward home.

[Fountain in Carré St-Louis, Montreal]

This brings me to the present moment. And, as Virginia Woolf asks in Orlando, "What more terrifying revelation can there be than that it is the present moment? That we survive the shock at all is only possible because the past shelters us on one side and the future on the other."

After a childhood spent in rural Nova Scotia dreaming of moving to Montreal and then fifteen years spent in Montreal writing of rural Nova Scotia, I had finally learned how to write about my small corner of Montreal, in the vernacular of neighbourhood, in the present moment. And then the whole neighbourhood changed.

My most recent work, in absentia [2008], addresses issues gentrification and its erasures in the Mile End neighbourhood of Montreal. in absentia is a Latin phrase meaning "in absence." I'm drawn to the contradiction inherent in being in absence. In recent years many long-time low-income neighbours being forced out of Mile End by economically motivated decisions made their absence. So far fiction is the best way I've found to give voice these disappeared neighbours, and the web is the best place I've found to situate their stories. Our stories. My building is for sale; my family may be next.

Faced with imminent eviction I've begun to write about the Mile End as if I'm no longer here, and to write about a Mile End that is no longer here. By manipulating the Google Maps API, I am able to populate "real" satellite images of my neighbourhood with "fictional" characters and events. I aim to both literally and figuratively map the sudden disappearances of characters, fictional or otherwise, from the places, real or imagined, where they once lived; to document traces people leave behind when they leave a place, and the stories that spring from their absence. in absentia is a web "site" haunted by the stories of former residents of Mile End, a slightly fantastical world that is already lost but at the same time is still fully known by its inhabitants: a shared memory of the neighbourhood as it never really was but could have been.

Faced with imminent eviction I've begun to write about the Mile End as if I'm no longer here, and to write about a Mile End that is no longer here. By manipulating the Google Maps API, I am able to populate "real" satellite images of my neighbourhood with "fictional" characters and events. I aim to both literally and figuratively map the sudden disappearances of characters, fictional or otherwise, from the places, real or imagined, where they once lived; to document traces people leave behind when they leave a place, and the stories that spring from their absence. in absentia is a web "site" haunted by the stories of former residents of Mile End, a slightly fantastical world that is already lost but at the same time is still fully known by its inhabitants: a shared memory of the neighbourhood as it never really was but could have been.What traces do people leave behind when they leave a place?

What stories spring from their absence?

Themes of place and displacement pervade my fiction and electronic literature, yet place long remained an abstract, elusive notion for me. Perhaps because for many years I wrote about long ago places attempting to inhabit pasts that could never be mine. Mapping the minutia of my most immediate surroundings has made my notion of place less abstract and more socially engaged. Increasingly, my work is collaborative. To better represent the multi-lingual nature of my neighbourhood and to ensure a multipule point of view, for in absentia I invited a cast of English and French writers from my neighbourhood to pen "postcards" to and from former tenants, fictional or otherwise, displaced by gentrification. in absentia was presented by DARE-DARE Centre de diffusion d'art multidisciplinaire de Montréal - an artist-run centre that operated out of a trailer parked in a park without a name on the northern-most border of Mile End until recently.

The mobile office has since the vacant lot that was its home for two years and move towards Montréal's downtown, in Cabot Square, corner Sainte-Catherine and Atwater. in absentia marked the end of DARE-DARE's Dis/location: projet d'articulation urbaine in the Mile End's parc sans nom. DARE-DARE was evicted by the city to make room for a parking lot. There goes the neighbourhood. Where we would park a garden so many people plant cars.

The mobile office has since the vacant lot that was its home for two years and move towards Montréal's downtown, in Cabot Square, corner Sainte-Catherine and Atwater. in absentia marked the end of DARE-DARE's Dis/location: projet d'articulation urbaine in the Mile End's parc sans nom. DARE-DARE was evicted by the city to make room for a parking lot. There goes the neighbourhood. Where we would park a garden so many people plant cars.

If, as Anne-Marie MacDonald suggests, "[when] you move around all your life, you can't find where you come from on a map," at least, through a sustained (stubborn) practice of writing and rewriting contingent stories of precarious past events it is possible, on occasion, to locate one's present location. Even if, in the very act of writing of it, one's present location becomes fictional.

"I packed my rucksack with socks, canteen, pencils, three empty notebooks. I took no maps, I cannot read maps - why press a seal on running water? After all, the only rule of travel is, Don't come back the way you went. Come a new way." Anne Carson, "The Anthropology of Water," in Plainwater, NY: Vintage, 1995, page 123.